“Is polling the DB every minute really a sin?” “Is event-driven architecture always the right choice?”

I’d like to share the design process behind our time-based notification architecture — a topic that sparked intense debate within the team while enhancing our notification system.

The Problem

Our system had the following time-based notification requirements:

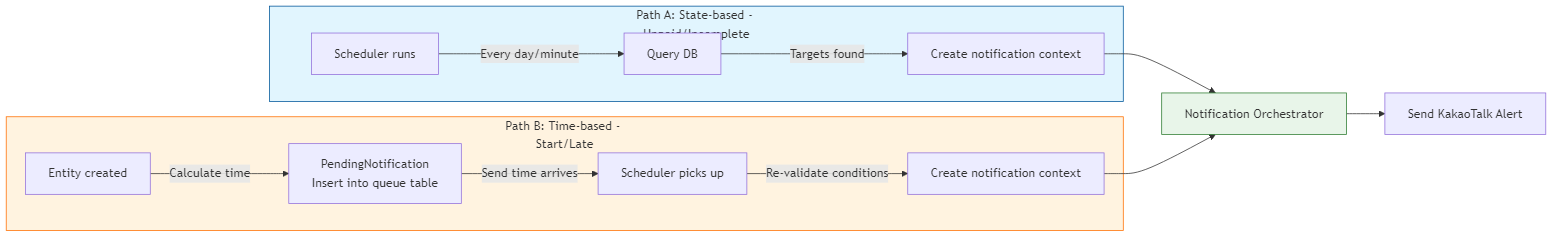

- Type A (Recurring Payment Reminder): Send at 09:00 the day after each billing date

- Type B (Daily Mission Incomplete): Send at a specific time on the deadline day

- Type C (Worker Start Reminder): Send 10 minutes before shift start

- Type D (Worker Late Alert): Send 5 minutes after shift start if not checked in

Two design options were pitted against each other to implement these requirements.

Round 1: Option A (Scheduler) vs Option B (Event Queue)

Option A: Dedicated Scheduler (Polling)

A scheduler runs every minute (or daily), finds targets that meet conditions, and sends notifications.

@Scheduled(fixedDelay = 60000)

public void checkLateWorkers() {

// 1. Query workers whose shift started 5+ minutes ago

// 2. Filter those who haven't checked in

// 3. Send notification

}

- Pros: Simple implementation with guaranteed data consistency. Since it queries the DB at runtime, there are no state mismatch issues like missed cancellations.

- Cons: The guilt of “hitting the DB every minute.” Performance issues (full scans, etc.) may arise as data grows.

Option B: Event Queue (PendingNotification)

Pre-schedule future notifications at the point when events occur (e.g., when a schedule is created).

// When schedule is created

pendingNotificationService.schedule(

userId,

"TYPE_D",

startTime.plusMinutes(5) // Schedule for delivery

);

- Pros: Triggers at the exact time with no unnecessary queries. Aligns with the elegant “event-driven” architecture.

- Cons: State Synchronization hell.

- Schedule changes? → Cancel and reschedule.

- Worker checks in early? → Cancel the pending notification.

- Miss a cancellation? → “I already checked in, why did I get a late alert?” (false notification incident)

Round 2: State-based vs Event-based Deep Dive

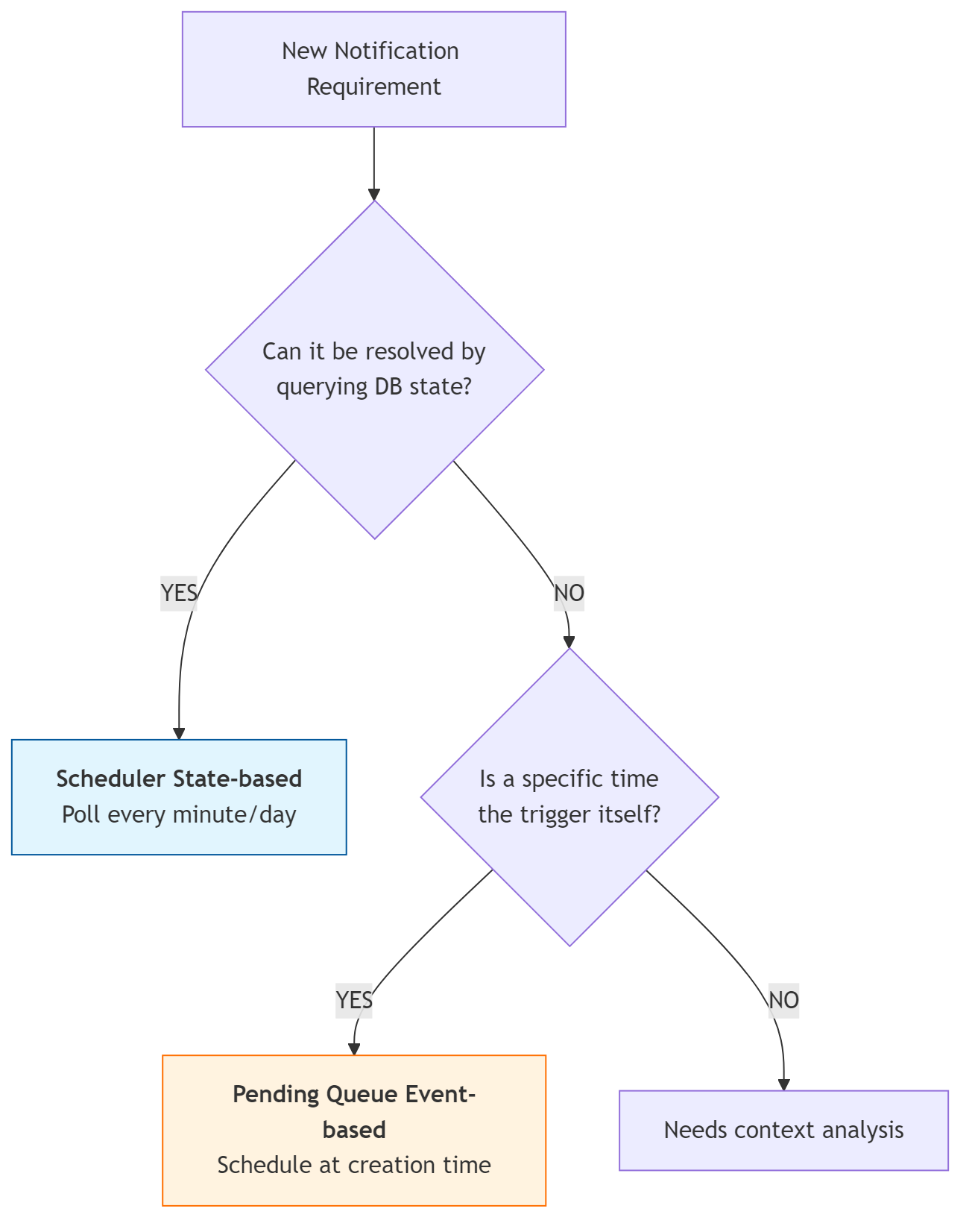

During discussion, a pivotal insight emerged: “We shouldn’t treat all notifications the same — we need to categorize them by nature.”

Here are the judgment criteria we established:

1. State-based Notifications

- Targets: Recurring payments (Type A), incomplete missions (Type B)

- Characteristic: It’s not about “when” — it’s about “what is the current state?”

- Conclusion: A scheduler (polling) is the right fit. Querying “who hasn’t paid yet?” every morning is the cleanest approach. Scheduling a notification then cancelling it upon payment is unnecessary complexity.

2. Event-based Notifications

- Targets: Pre-shift reminder (Type C), late alert (Type D)

- Characteristic: A clear trigger point exists — “shift start time.”

- Conclusion: Architecturally, an event queue (pending) is the right approach.

If you tried to implement this with a scheduler, you’d need to run this monstrous query every minute:

SELECT ws.* FROM work_schedules ws

WHERE ws.start_time - INTERVAL 10 MINUTE BETWEEN :now AND :now + 1min

AND NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM attendance_logs WHERE ...) -- Already checked in?

AND NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM leave_requests WHERE ...) -- On leave?

With the event queue approach, the logic becomes much cleaner: “calculate time at creation + validate conditions at send time.”

Round 3: Ideal vs Reality

But then the issue of “real-world engineering cost” was raised.

“I agree that the event queue (Pending) is architecturally correct. But our

PendingNotificationtable was designed as a simple batch processor. Supporting individual schedule/cancel/modify operations would require rebuilding the infrastructure from scratch.”

[Deep Dive] How Do Java Schedulers Actually Work?

The biggest misconception during the discussion was that “the scheduler stares at the clock every second, burning CPU (busy waiting).” But modern OSes and Java are smarter than that.

1. Taxi Drivers (Threads) and the Dispatcher (Executor)

Inside ThreadPoolTaskScheduler, there are idle threads (taxi drivers) and a queue managing them (the dispatcher).

- The dispatcher checks the next scheduled task time (09:00).

- If it’s currently 08:50, the dispatcher tells the OS “wake me up in 10 minutes” and goes to sleep (Wait).

- The thread enters

PARKstate — CPU usage drops to zero.

2. The Magic of Hardware (OS Timer Interrupt)

So who wakes it up? The computer’s heartbeat (Clock).

- The motherboard’s quartz oscillator sends an electrical signal (interrupt) to the OS every ~1ms.

- The OS only briefly wakes up on these signals to check: “anyone to wake up?”

- When 09:00 arrives, the OS shakes the sleeping Java thread awake (Notify).

Conclusion: Even with 100 registered schedulers, zero system resources are consumed until execution time. This is why you shouldn’t feel excessive guilt about “per-minute polling.”

In-memory Java Scheduler vs DB-based Queue

Question: “Can’t we just use Java’s in-memory scheduler?” Answer: No. If the server restarts, all scheduled notifications vanish (volatile). Production services require a persistent, DB-based queue.

The debate ultimately came down to: “Build a proper DB-based scheduling system (like Quartz)” vs “Handle it with the existing scheduler.”

Final Decision: Phased Approach

We chose pragmatism.

Hybrid Architecture

Phase 1: All Scheduler (Right Now)

- Implement all notifications (Types A, B, C, D) using scheduler polling.

- Rationale:

- At our current traffic level (single instance), per-minute polling overhead approaches zero.

- We can deploy immediately by writing only business logic — no infrastructure buildout needed.

- It’s the safest option for data consistency. (Source of Truth = DB)

Phase 2: Hybrid (Future)

- When traffic explodes or attendance data grows too large for polling to handle?

- Then we’ll extract Types C and D into an enhanced pending notification system.

[Comparison] Playing in the Big Leagues (High Traffic)

What if we were operating at Naver or Kakao scale?

1. Kafka Delay Queue (Large-scale Event-driven)

- Pattern: Instead of sending messages directly to consumers, place them in a separate ‘Delay Topic.’

- Mechanism: When a consumer reads a message, it checks the timestamp. If it’s “not time yet,” it defers or waits briefly.

- Pros: Massive throughput and scalability.

- Cons: Very high implementation complexity. (Partition management, offset commits, etc.)

2. Redis Sorted Set Delay Queue (The Startup’s Best Friend)

- Pattern: Leverages Redis’s

ZSETdata structure. - Command:

ZADD delay_queue <timestamp> <job_id> - Mechanism: Uses the score as the ‘scheduled send time (Unix timestamp).’ A scheduler fires

ZRANGEBYSCORE delay_queue 0 <now>every second, pulling out all jobs whose time has passed. - Pros: Easy to implement and extremely fast. Dramatically reduces DB load.

- Cons: If Redis goes down, scheduled notifications can be lost (AOF/RDB configuration required).

Our team’s choice: For now, an RDB (MySQL/PostgreSQL) based

PendingNotificationtable is sufficient. With proper indexing, RDB is the safest and most manageable queue for up to hundreds of thousands of records.

Takeaway

- “Simple is Best”: Complex architectures (event-driven) aren’t always the answer. Choose the right technology for your scale.

- Source of Truth: Always double-check the DB right before sending a notification.

- OS Secrets: A scheduler running every minute doesn’t mean 100% CPU usage. Thanks to OS timer interrupts (hardware timer interrupts) and thread wait/notify mechanisms, virtually no resources are consumed during idle time.

Bottom line: What matters more than architectural elegance is “Does it work right now, is it safe, and is it maintainable?”

References

- Polling vs Event-Driven:

- Understanding push vs poll in event-driven architectures - TheBurningMonk

- Event-Driven vs. Polling Architecture - Design Gurus

- When to use Polling vs Webhooks - Zapier Engineering

- Java Scheduler Internals:

Comments