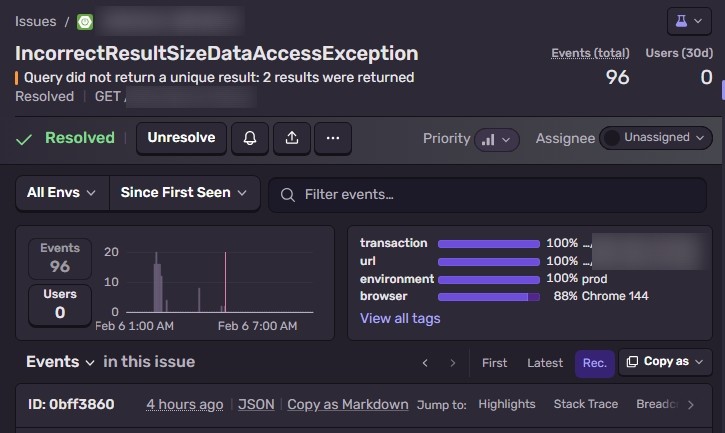

11 AM. Sentry alert.

NonUniqueResultException: Query did not return a unique result: 2 results were returned

96 times. Escalating. The booking status dashboard was completely down. It was coming from the status API (GET /rooms/status).

Following the stack trace Sentry captured, the culprit was a JPA query called findCurrentRoomBooking. Declared with Optional<RoomBooking> — meaning it expects 0 or 1 result — but it was returning 2, and crashing.

A query returning 2 results when it should return 1 means there’s duplicate data in the DB that shouldn’t exist. This wasn’t just a query bug — it meant the system’s fundamental assumption, “no overlapping bookings for the same room,” had been violated.

But the service already had overlap validation. Every create/update path checked for time conflicts and threw an exception if found.

So how did duplicate data get past the validation?

Step 1: Finding the Culprit

First, I queried the DB directly for overlapping bookings.

SELECT a.id, b.id, a.room_id, a.day_of_week,

a.start_time, a.end_time, b.start_time, b.end_time

FROM room_booking a

JOIN room_booking b

ON a.room_id = b.room_id

AND a.day_of_week = b.day_of_week AND a.id < b.id

AND a.start_time < b.end_time AND b.start_time < a.end_time

WHERE a.booking_type = 'MEETING_ROOM'

AND b.booking_type = 'MEETING_ROOM';

Exactly 1 result. Room 3A on Friday had two overlapping bookings.

| id | Time | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 301 | 09:00-12:00 | Has history |

| 309 | 10:00-11:30 | No history |

Step 2: Tracing the History

id 301 had a normal creation history. The problem was id 309 — no history at all.

Digging through the change log table revealed a clue.

201 | CREATE | 3A [Fri] 09:00-12:00 | 05:40:08.684 | booking_id=301

203 | CREATE | 3A [Mon,Wed,Fri] 10:00-11:30 | 05:40:08.690 | booking_id=305

History 203 shows “Mon,Wed,Fri 10:00-11:30” but only records booking_id=305 (Monday). The bulk booking API created 3 bookings at once for Mon/Wed/Fri, but only logged history for the first one. id 309 (Friday) was the third in that bulk creation — a ghost invisible in the audit log.

And look at the timestamps — the gap between the two histories is 0.006 seconds.

Step 3: The 0.006-Second Mystery

No human clicks twice in 0.006 seconds. The code was firing requests in parallel.

The frontend was sending API calls in parallel when saving multiple time slots. On the server, each request ran as a separate transaction. Under MySQL’s default REPEATABLE READ isolation level, uncommitted data from other transactions is invisible.

Request A: [──overlap check──][──save──][commit]

Request B: [──overlap check──][─────save─────][commit]

↑

At this point, Request A hasn't committed yet

→ overlap check passes

The validation logic was perfect. Within a single transaction. The problem was visibility between concurrent transactions.

I understood the cause. But fixing the root cause meant redesigning the API — the architecture of sending multiple time slots as separate requests was the real problem. That would take time.

What needed to be fixed right now was something else — the dashboard was on its 96th crash.

Immediate Response: Turning Crashes into Warnings

I knew why the duplicate data got in. Fixing the root cause comes next. The urgent priority was making the service survive when impossible data exists.

The crashing JPA query had Optional<RoomBooking> as its return type. When 2+ results come back, JPA throws NonUniqueResultException. Nobody caught it, so the entire API returned 500.

The fix is simple. Change the return type to List, and send a Sentry WARNING when duplicates are detected.

// Before — crashes on duplicate data

Optional<RoomBooking> booking = repository

.findCurrentRoomBooking(roomId, dayOfWeek, time);

// After — service continues even with duplicates

List<RoomBooking> bookings = repository

.findCurrentRoomBooking(roomId, dayOfWeek, time);

if (bookings.size() > 1) {

log.warn("Duplicate room booking detected - roomId: {}, day: {}, time: {}",

roomId, dayOfWeek, time);

Sentry.captureMessage(

"Duplicate room booking detected - roomId: " + roomId,

SentryLevel.WARNING);

}

return bookings.isEmpty() ? null : bookings.get(0);

Now if the same situation happens again:

- Service stays alive. Uses the first result and responds normally.

- Alerts still come. Sentry WARNING detects duplicate occurrences.

- Cleanup is possible. Receive the alert, clean up duplicate data from DB.

96 crashes become 1 warning.

Side Fix: The Audit Log Blind Spot

There was a reason the root cause investigation took so long. id 309 had no history at all, making it impossible to trace where the data came from.

When creating bulk bookings for Mon/Wed/Fri, history was only recorded for the first one (Monday). The thinking was probably “one representative record is enough” — but from an incident investigation perspective, it was a critical blind spot.

I updated bulk creation to log individual history for every record. The cost of one extra log line is far less than the cost of being unable to trace the cause during an incident.

The Root Cause Was Fixed Later

After deploying the defensive query and stabilizing the service, I addressed the root cause. The architecture that sent multiple time slots as individual API calls was redesigned into a Multi-Slot API that sends all slots in a single request. The server handles cross-slot validation within a single transaction, making the race condition structurally impossible.

Initially, I thought adding await to the frontend to serialize requests was the fix. But that was a workaround, not a root cause solution. The answer wasn’t “send multiple requests in order” — it was “make it one request in the first place.”

Lessons Learned

1. Stabilize first, fix root cause second

When production is crashing, don’t try to redesign the API to fix the root cause. Stop the bleeding first, then fix the cause. In this case, changing one return type was enough to save the service.

2. Optional doesn’t guarantee a single result — it enforces it

JPA’s Optional return type throws an exception when the “0 or 1 result” assumption breaks. Even if business logic expects a single result, if there’s any chance of data integrity violation, receiving a List and handling it defensively is safer.

3. Sentry is a monitoring tool, not just a discovery tool

Sentry played two roles here:

- Discovery: Alerted us to the incident with 96

NonUniqueResultExceptionevents. - Surveillance: After the fix,

captureMessage(WARNING)continues monitoring for duplicates.

Catching thrown errors is important, but sending WARNINGs for “not an error but needs attention” situations is an essential Sentry usage pattern.

4. Audit log blind spots block incident investigation

When bulk operations only log “one representative record,” the rest become untraceable. This literally blocked root cause analysis in this incident. Logs must be comprehensive.

Even with perfect validation logic, data can break. Whether the service crashes or sends a warning comes down to one line of defensive code.

Comments